Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Middle Eastern politics & society myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

“There are only two of us left among the leaders. Right now, it’s me and Vladimir Putin.” That was the immodest verdict of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan last week.

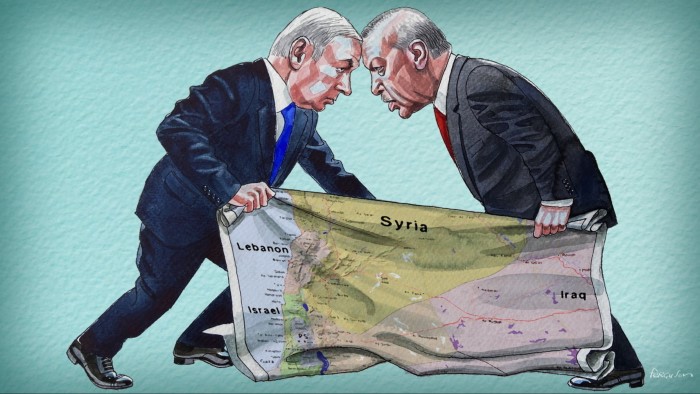

Xi Jinping and Donald Trump might dispute the Turkish president’s global rankings. At a regional level, however, Erdoğan has a good claim to be one of two strongman leaders that are reshaping the Middle East. His hated rival, Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, is the other.

Erdogan’s current arrogance flows from his role in Syria. Turkey was the only regional power to put its full weight behind Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, the Islamist group that toppled the Assad regime. Ibrahim Kalin, the head of Turkey’s intelligence services, visited Damascus days after HTS took power.

Erdoğan has long aspired to rebuild Turkish power across the territories of the old Ottoman Empire. For him, toppling Assad opens a new path to regional influence. It also potentially has a domestic pay-off — weakening the Kurds in Syria, easing Turkey’s refugee problem and helping his bid to stay on as president after 2028.

Turkey’s alliances with Islamist groups like HTS and the Muslim Brotherhood are regarded as a serious threat by Israel and the conservative Gulf monarchies. Israel has moved to destroy Syria’s military capacity, bombing its navy and air force and seizing territory beyond the Golan Heights, which Israel has occupied since 1967.

The Israeli government portrayed its moves as precautionary and defensive. But Netanyahu, like Erdoğan, sees opportunities ahead. Speaking last week, he remarked: “Something tectonic has happened here, an earthquake that hasn’t happened in the hundred years since the Sykes-Picot agreement.” That reference to the 1916 British-French agreement that divided up the Ottoman Empire sounds significant. With the Middle East in turmoil, advocates of a Greater Israel see a chance to redraw the region’s borders again. Aluf Benn of Haaretz writes that Netanyahu “seems to be angling for a legacy as the leader who expanded Israel’s borders after 50 years of retreat”.

The settler movement, well represented in Netanyahu’s coalition government, is pushing for Israel to reoccupy parts of Gaza. The incoming Trump administration may give Israel the green light to formally annex parts of the occupied West Bank. And the “temporary” occupation of Syrian land may prove to be permanent.

Further afield, Netanyahu will see an opportunity for a final reckoning with Iran. The Islamic Republic is in its weakest position for decades. It faces domestic opposition and will be unsettled by the fall of Syria’s autocracy. Tehran has seen its allies — Hamas, Hizbollah and now Assad — devastated.

Iran might respond to the loss of its regional proxies with an accelerated drive to obtain nuclear weapons. But that could invite an attack by Israel. After the Netanyahu government’s successful offensive against Hizbollah in Lebanon — a campaign that the Biden administration warned against — the Israelis are in a confident, radical mood.

Over the past year, Israel has demonstrated its ability to fight on multiple fronts simultaneously — including Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, Yemen, Iran and now Syria. The Israelis are also the only nuclear-armed power in the region and, for now, have the almost complete backing of the US.

Netanyahu’s chances of going down in history as a successful leader seemed slim after the catastrophe of the October 7 attacks by Hamas. Deeply controversial at home as well as abroad, he is currently on trial for corruption in Israel.

Like Erdoğan, Netanyahu is a ruthless political survivor. Each first took power decades ago and regards himself as a man of destiny. However, their dreams of regional dominance suffer from similar weaknesses. Israel and Turkey are non-Arab powers in a majority-Arab region. There is no appetite in the Arab world for a recreated Ottoman Empire. Israel remains an outsider power in the Middle East, feared, distrusted and often hated.

Turkey and Israel also have too weak an economic base to genuinely aspire to regional dominance. The Turkish economy is ravaged by inflation. For all its technological and military prowess, Israel is a small country of fewer than 10mn people.

The rival ambitions of Erdoğan and Netanyahu could easily clash in Syria. It risks becoming a battleground for competing regional powers because Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries also have interests at stake there.

Last week, as the Turks were cheering the fall of Damascus and the Israelis were destroying the Syrian military, Saudi Arabia celebrated a more peaceable achievement, being chosen as hosts of the 2034 World Cup.

The Saudis and the Gulf states probably feel more directly threatened by Turkey’s Islamist alliances than by Israel’s territorial ambitions. But Riyadh knows that Israel’s assault on Gaza has appalled much of the Arab world. Moving closer to Netanyahu to block Erdoğan would be controversial, particularly if the Israelis are simultaneously burying any prospect for a two-state solution with the Palestinians.

Israel and Turkey have powerful militaries. But the Saudis, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have the financial firepower. Whatever course Riyadh decides to take could shape the Middle East even more fundamentally than the actions of Erdoğan and Netanyahu.

gideon.rachman@ft.com