By Chris Snellgrove

| Published

Star Trek is a franchise with plenty of dialogue that has become part and parcel of our shared pop culture, and even non-fans are prone to saying things like “He’s dead, Jim” or “beam me up.” However, one veteran Trek writer thinks that an overlooked conversation in a largely forgotten episode might be one of the franchise’s greatest moments. According to prolific novelist J.M. Dillard, a quick conversation between Commander Sisko and Dr. Bashir in the Deep Space Nine episode “The Forsaken” made TV history by subverting the usual racist depictions of onscreen characters in the ‘90s.

The Conversation

The conversation starts when Bashir visits Sisko’s office to talk about the doctor’s task of escorting annoying alien ambassadors around the station. In Star Trek – Where No One Has Gone Before, Dillard admits that “there’s nothing unusual about this conversation” because “it’s the kind that goes on every day in offices all over the world.” However, “the difference is that when a Black man is talking to a Middle Eastern man in a typical television drama, they are almost certain to be talking about drugs, crime, terrorism, or violence–and are most likely to be presented as uneducated, heavily accented, immoral, or antisocial–but never on Star Trek.”

To younger fans born after Deep Space Nine came out, Dillard’s claim may seem a bit hyperbolic, but it’s worth remembering that this show very deliberately centered on issues of race from the very beginning. Avery Brooks’ Sisko was the first Black lead in a Trek show and remained the only one until the premiere of Discovery. Later DS9 episodes would explore race and racism very directly, including “Far Beyond the Stars,” an episode revealing that the entire show might be an invention of Benny Russell, a sci-fi writer facing extreme (and very ugly) racism in 1953 America.

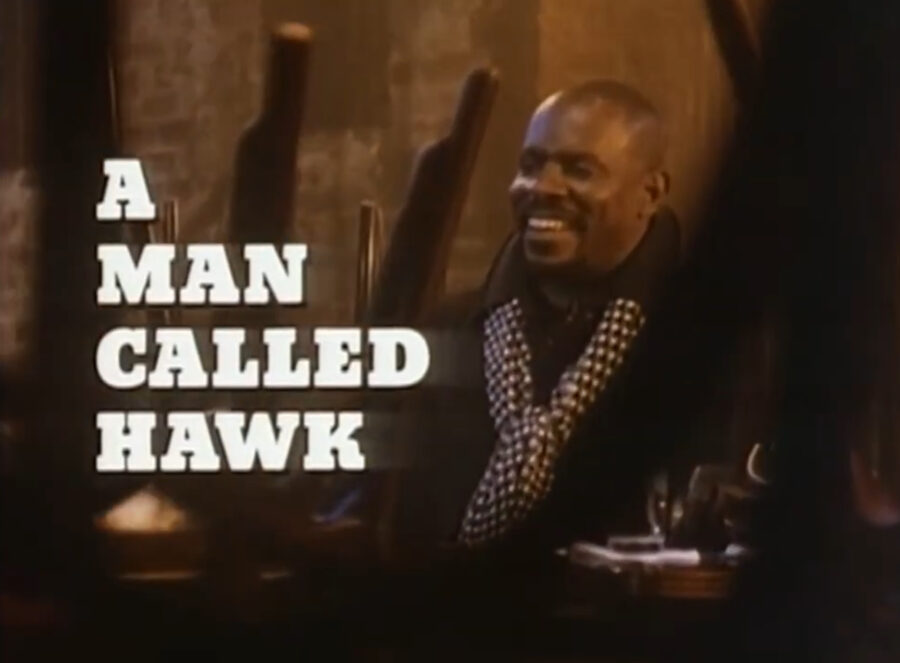

Such storytelling might seem on the nose now, but the Deep Space Nine writers felt it was necessary because Dillard was right: far too many Black characters in the ‘80s and ‘90s were portrayed as dangerous thugs rather than righteous heroes. Brooks, for example, was presented sympathetically in his breakout role in Spenser for Hire, but his character of Hawk was still a largely unscrupulous hitman who often seemed written as more of a racist caricature than a character.

Whether Hawk was a tokenized or trailblazing character is certainly up for debate, but Brooks himself later noted that his portrayal caused many white fans to assume that he really was a gun-toting guy whom the producers recruited from “a street corner somewhere.” He said that some of those same fans “talk to me in some vernacular that’s supposed to be, what, black speech?” Hollywood wasn’t much better than these fans: while DS9 was still on, he starred in The Big Hit, a big-budget film where he portrayed (what else?) a violent mob boss.

From the beginning, Deep Space Nine centered on race with its human characters and its aliens. For example, the story of Cardassians using Bajorans as slave labor on the titular space station is clearly evocative of America’s troubled racial history. And Brooks was never afraid to step in and speak to the writers when he thought they might accidentally be feeding into racial stereotypes. This is most evident in the series finale: Brooks insisted that Sisko tell his pregnant wife Kasidy Yates that he would return someday because he was uncomfortable with a story about a Black man abandoning his wife to raise their child alone.

As Dillard notes, though, the real magic of Deep Space Nine is that it can tell stories about race that nonetheless don’t always make a big deal about the whole thing. Even at its most preachy, the show never feels like we’re being lectured to via an ‘80s-style “very special episode.” Instead, DS9 presents characters of all races with dignity and professionalism, showing us that a better tomorrow is about more than replicators and warp drives. It’s also about leaving our old hangups and prejudices in the past as we reach toward a better future for everyone regardless of the color of their skin.